Download our Teen Driving Study

Now!

Download our Teen Driving Study

Now!

In recent years, many surveys have been conducted of teenage drivers in order to obtain a better understanding of their distracted driving behaviors and to develop strategies for addressing those behaviors.

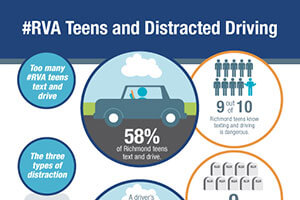

However, most surveys have been done at a national level. This survey focused on teen drivers living in a specific community – the metropolitan area of Richmond, Virginia.

In this study, we conducted an online survey in March 2015 of high school students from within the Richmond community. A total of 238 teens participated in the study. However, 15 teens were excluded from our analysis of the survey results because they reported that they had not yet started driving.

Sara Richter, M.S., a Senior Statistician at Park Nicollet Institute, analyzed the survey data and made the following important findings:

These findings indicate that a main method of addressing the dangers of distracted driving is to direct strategies towards parents. The parents of teen drivers should be strongly encouraged to talk with their children about distracted driving behaviors, and they should be provided with resources that can help them to engage in this important discussion.

Distracted driving is dangerous, especially for new drivers. An annual report by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) showed the number of people killed in car crashes involving a distracted driver has held steady in recent years, while the number of crashes with injuries involving distracted drivers has risen. (See chart).

| Year | Injuries | + / - | Change | Fatalities | + / - | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 387,000 | --- | --- | 3,360 | --- | --- |

| 2012 | 421,000 | + 34,000 | 8.1% | 3,328 | - 32 | 1.0% |

| 2013 | 424,000 | + 3,000 | 0.7% | 3,154 | - 174 | 5.2% |

These numbers indicate that approximately nine people die and 1,000 are injured on a daily basis in distracted driving accidents.

In the U.S., teenagers (ages 16-19) drive fewer miles than other age groups. However, their fatal crash rate per mile driven is nearly three times the rate for drivers ages 20 and older. The risk of a fatal crash is highest at ages 16-17, with the fatal crash rate per mile driven among drivers in this age group being almost double the rate for 18-19 year-olds. Among all drivers ages 15-19 involved in fatal crashes, 10% were reported as distracted at the time of their crash – the highest rate of distracted driving across all age groups.

While many forms of distraction exist, cell phone use, especially texting, can be the most dangerous. This is because texting while driving involves the three main types of distraction:

Taking your eyes off the road

Taking your eyes off the road

Taking your hands off the wheel

Taking your hands off the wheel

Taking your mind off of driving

Taking your mind off of driving

Many studies have been done on the effects of texting while driving. Research by the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute has shown that text messaging is associated with the highest risk of all sources of distraction. Some of the most impactful results are:

Even though teenagers are aware of the dangers, they still choose to text and drive, and many engage in other risky driving behaviors. When asked, 97% of teens in a 2012 survey by AT&T reported that texting and driving was dangerous, and 75% said it was very dangerous. Despite the known dangers, 43% of those same students reported texting and driving anyway.

In a similar survey, the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety found that 35% of those ages 16-18 reported reading a text message while driving, and 27% admitted to writing/sending a text. Moreover, approximately 8% of young drivers in that study believed it was acceptable to text and drive – the highest percent of any age category.

Additionally, a recent study by Olsen, et al., found that teens who text while driving are more likely to not always wear their seatbelt, ride with a driver who has been drinking alcohol and to drink alcohol and drive.

Many organizations have tried to spread awareness of the dangers of texting and driving and implement measures to reduce texting while driving. For instance, text messaging while driving is banned for all drivers in 45 states and the District of Columbia. It is also banned for young drivers in an additional three states.

Celebrities such as Justin Bieber and Jordin Sparks have spoken out about the dangers of texting and driving. Phone companies like AT&T have run graphical TV campaigns featuring family members of deceased distracted drivers.

In addition to these legal and marketing approaches, many cell phone and other technology companies have promoted technology to prevent texting and driving, using apps such AT&T's DriveMode, DriveScribe and Drive Safe.ly.

With all of these resources available to prevent texting while driving and the problem continuing to grow, more information is needed to determine specific texting and driving habits of teenagers.

A 27-item questionnaire was administered to teens from high schools located in the Richmond, Virginia area via SurveyMonkey. Participants who completed the survey were entered into a drawing for a mini iPad.

Prior to analysis, data were cleaned. When looking for consistency of answers, it was found that 20% of teens who reported never texting and driving actually did text and drive.

Although there were only 24 questions related to texting and driving, most had multiple response options where participants could select all that apply. As the options were sometimes related, new groups were created. Definitions of these new groups are below.

A few of the questions within the survey could not be used in analysis. These questions had ambiguity in the question they were asking, overlapping or missing responses or directions that did not match the answer choices (i.e. the question indicated the respondent could "check all that apply," but the survey program allowed for only one answer to be selected). The specific questions and their concerns are outlined below.

It is unclear if "it" refers to the number of texts or the number of driving segments where at least one text was sent. Also, the survey did not provide a zero, "Not Applicable" or "I don't text and drive" response for the students who indicated they never text and drive.

The survey did not provide an "I don't see other drivers texting while driving" response option. This question would have been better placed after the question "Have you seen people in other cars who are texting while driving?"

The instructions for this question say to check all that apply. However, the survey was set up so participants could choose only one response. Also, the response options actually get at four different questions related to the ads – do you pay attention to them, did you change behavior because of them, did they give you enough information and what was your perception of them.

Descriptive summaries were generated using SAS v 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Where appli- cable, chi-square tests were used to identify statistical significance. P-values (p) are statistically significant if p <0.05 and are considered marginally significant/trending if p <0.10.

A total of 238 participants responded to the survey. Of those, 15 (6.3%) indicated they had not started driving yet. They were excluded from the data analysis, which left 223 participants in the dataset for analysis. The survey set-up may be why many participants did not reveal their gender or driving experience.

| Gender | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 87 | 39% |

| Male | 51 | 23% |

| Did not respond | 85 | 38% |

| Driving Experience | Number | Percentage |

| Less than 1 year | 75 | 34% |

| 1-2 years | 39 | 17% |

| 2-3 years | 9 | 4% |

| More than 3 years | 15 | 7% |

| Did not respond | 85 | 38% |

Overall, 129 out of the 223 (58%) teens reported texting while driving. Teens who do not text and drive were also less likely to talk on their cell phones while driving than teens who do text and drive (30% vs. 83%, p <0.001).

When looking at the specific texting behaviors of those who do text and drive, most teens who text while driving were:

There was no difference in the overall rate of texting between males and females. However, when looking at specific uses of the phone (texting only vs. texting, sending pictures and using apps), males were more likely to send only text messages compared to females (91% vs. 76% - not statistically significant). Thus, females were more likely to text, send pictures and use apps than males.

In this study, 94% of teens knew texting while driving is dangerous, and 93% knew there was a text ban for all drivers in Virginia. However, 58% still reported texting while driving. This is a higher percentage of teens than in previous studies (43% AT&T; 45% Olsen, et al.). This increase could be due to the sample (the teens came from only one area in Virginia vs. national surveys), or it could be due to texting while driving simply happening more often than previously indicated.

The teens who do not text and drive reported having more discussions with parents, teachers and driver's education instructors about the dangers of texting and driving than the teens who do text and drive (p=0.03). In fact, 41% of teens who do text and drive said no one discussed texting and driving with them compared to 23% of teens who do not text and drive.

Approximately 50% of parents discussed the dangers of texting and driving with their kids. Interestingly, teens whose parents did discuss texting and driving were less likely to text and drive than teens whose parents did not discuss it with them (52% vs. 64% text and drive, p = 0.07).

Even though some teens still chose to text and drive, those with a parental discussion more often only texted (88%) than their peers who did not have a parental discussion (70%, p = 0.04). So, those without a discussion more often chose to send pictures or use apps.

Based on the survey data, parental texting while driving did not relate to whether the teens texted and drove. In many other studies, teens are more likely to text and drive if their parents do as well. Additionally, parental texting while driving also did not relate to the specific texting behaviors of the teens who do text and drive.

Approximately 21% of teens reported texting only their parents. The other 79% reported texting peers only (friends, classmates and/or co-workers) or both peers and parents.

The teens who reported texting only their parents:

There were too few teens (n=9) who reported texting while their parents were in the car to report on their behaviors.

About 40% of the teens who texted and drove said they did so in higher risk driving conditions. The students who text in higher risk situations tend to use their phones more (send pictures, use apps, etc.) while those in lower risk situations tend to text only (31% compared to 13% of lower risk texting teens who use apps/pics; p=0.04).

The students who text in lower risk conditions only do so because they believe it is safe more often that those who text in higher risk conditions (72% vs. 23%; p <0.01). That is, 77% of students who said they text in higher risk conditions:

Those who text in lower risk conditions are more likely to do so while they are alone in the car, while those who text in higher risk conditions tend to do it regardless of who is in the car with them (p=0.08).

The teen drivers who text while driving are more likely to do so as they become more experienced drivers. That is, only 37% of teens with less than one year of driving experience texted while driving, compared to 71% of those with more than one year of driving experience (p = 0.001).

The specific texting behaviors (i.e. driving conditions, when they text, who they text, who is with them in the car when they text, etc.) were similar between drivers with less than one year of driving experience and those with one or more years of driving experience.

The results of this study underscore the important role that parents play in raising teens' awareness of the dangers of distracted driving. By having a discussion with their teen driver about topics such as texting while driving, parents can strongly influence whether their child engages in such risky behavior.

The following are resources that may help parents to engage in this needed conversation: